A short film about killing | A short film about love

the centerpieces of Dekalog (and human interactions)

It would seem unreasonable to explore A short film about killing and A short film about love out of the context of the TV show Dekalog: the two films are none other than the theatrical extended versions of the middle episodes of the miniseries (even if between VI and Love the differences are significant). Yet, that is how they appeared to the public: these two films started to run through festivals internationally a year before Dekalog, in 1988, and as a result, had their own impact.

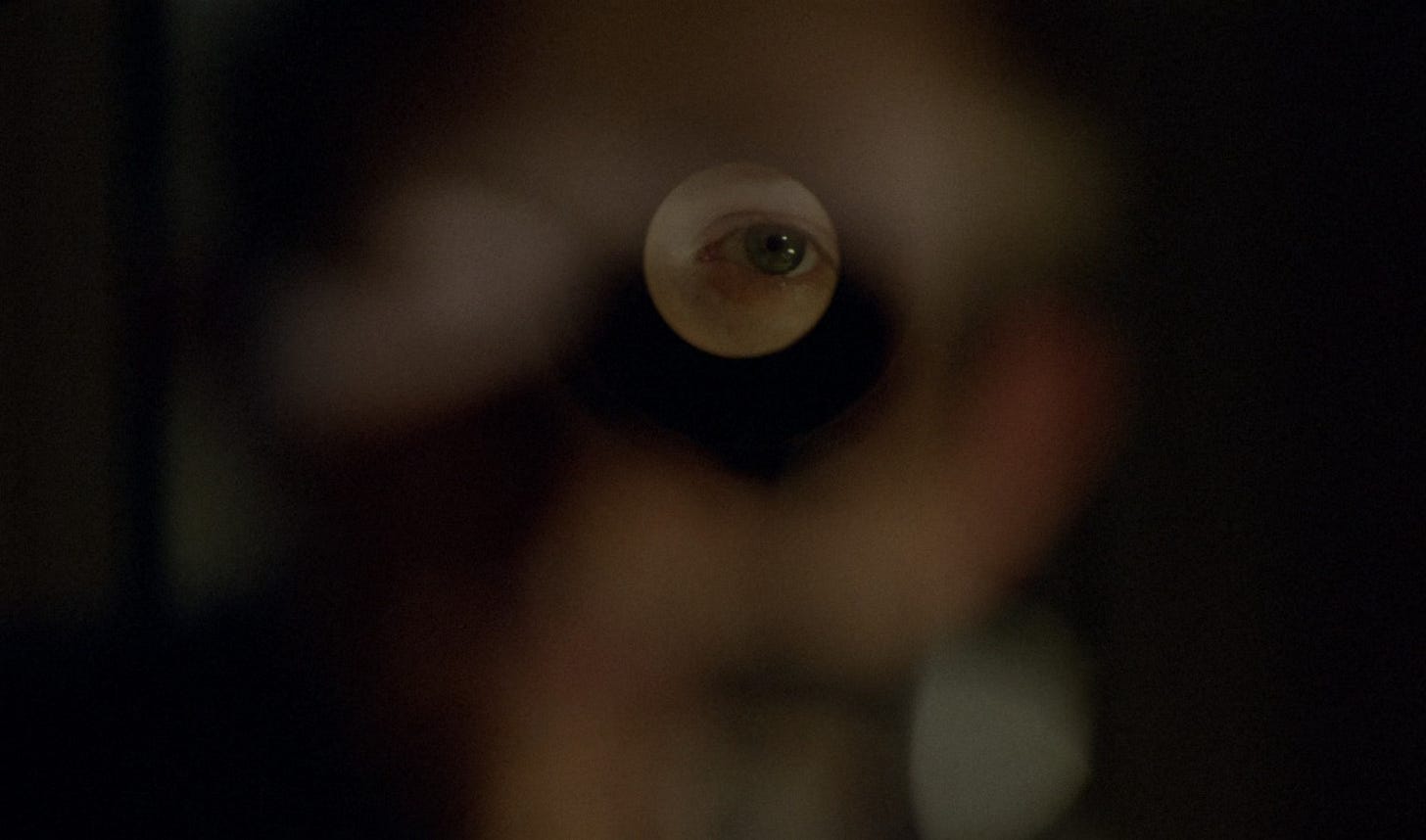

In the framework of Kieslowski’s series dedicated to the biblical ten comandaments and their influence in contemporary society, these two films examine the comandaments “thou shalt not kill” and “thou shall not commit adultery” (in religious terms, extramarital sexual activities in general). What immediately the titles catch is a sort of polarity between these two comandaments: murder and lovemaking are, in social interactions, on the very opposite sides of the spectrum. Therefore, through the two extremes, Kieslowski’s “short films” end up exploring the very essence of human sociability.

Much like all of Kieslowski’s work can be interpreted beyond its intended scopes back then, what’s interesting in the pairing of these films is that their protagonists, Jacek (A short film about killing) and Tomek (A short film about love) have a strikingly similar profile: both are nineteen years old, outsiders (one, a drifter, the other, an orphan), both seem disconnected by social conventions (objectively, Tomek does not commit a murder, but surely performs enough actions to deserve a restraining order at the very least), and most interestingly, both, have an anormal attitude towards women. It seems like Jacek and Tomek are representative of the same form of masculinity, curbed by a series of social expectations, inherently emotionally fragile.

Could we speak of toxic masculinity? It is the years when the term starts to be employed in psychologycal studies, afterall, but Kieslowski’s examination of his protagonists is not hostile, but rather sympathetical, and goes deeper than labels. Jacek and Tomek are affected by a masculinity that is unhealthy, but it would be reductive to describe them as merely toxic. Tomek is sincerely drawn by an attraction that he describes as love, Jacek is sincerely aware of the unethical nature of his actions, but both are tormented souls, influenced by the pressures of a societal norm that shapes them but they don’t seem to belong to.

What makes A short film about love specifically interesting in comparison to Dekalog VI is how the two films have few, but profound differences in the continuity of the storyline, that affect the emotional aspects of the films. The theatrical version adds a sequence in which Tomek’s immaturity is further expressed, and an ending that turns to explore Magda’s own feelings. In Dekalog VI, it was apprehension, in A Short film about Love, the film asks whether there is more to it: can her apprehension be love? Another interesting difference is that of the circularity of the space in Dekalog VI: the film starts and ends at the post office. Curiously, the episode might appear as more harmonious than the tv show, given its more grounded narration. Also, Dekalog V and A Short film about Killing do not share this sort of differences.

A Short film about Killing, today, is perceived as one of the few films capable of political change. Its release amidst a debate centered on death penalty in Poland, the suspension of the practice around the time when the film was screened, make for an interesting association, hard to quantify effectively. There has been a similar case with Agnieszka Holland’s Green Border recently, released amidst elections in Poland and that seems to have resonated with a silent majority that determined the victory of the opposition, again, an unquantifiable influence, but that confirms that perhaps, in Poland, films do have a political weight. When we look at Dancer in the Dark by von Trier, Into the abyss by Herzog or even True Crime by Eastwood — effectively decades of films about the death penalty in the United States — and the fact that their brought no political result of any kind, the comparison is very notable.

Two films that somehow encompass the essence of Kieslowski, in all aspects: the potentiality, as they work independently or grouped with other films, provoking all sorts of meanings and interpretations; the scope, as one is exploring the darkest corners of the human soul, the other its most tender ones; the deep, emotional toll.

-

Original title: Krótki film o zabijaniu | Krótki film o miłości

Directed by: Krzysztof Kieslowski

Country: Poland

Year: 1988

Length: 84 min | 87 min

Availability: Criterion Channel, etc.